Happiness is not a Matter of Having, but a Matter of Being.

by Doug McManaman

Until recently I was very engaged in a discussion on an Internet forum that dealt specifically with the issue of Assisted Suicide. Our discussion of the fundamentals of ethics went on for quite a few months, and they were for the most part discussions with very intelligent people. Three of them, with whom I argued till the very end (if the end has in fact arrived, which I somehow doubt) are mechanical engineers. But what strikes me about the entire affair is how simple the contending moral positions can be divided and summed up. Everyone on the forum falls into one of only two "schools", so to speak. Those who believe that their own private wills are the measure of what is right and wrong, and those who believe that God is the measure of what is right and wrong. "My will be done" versus "Thy will be done". That just about says it all.

Now many of them would deny this. They would counter my claim by reminding me that it is social consensus that determines what is right and wrong. And this is true. Many of them indeed argue that it is social consensus alone that is the ultimate measure of what is right and wrong, and that there is no need to appeal to any higher law, which would imply the existence of a higher being.

But I have often pointed out to them that society has already spoken with regard to the issue of Patient Assisted Suicide (PAS). Jack Kevorkian is in jail. And the Supreme Court of the United States has ruled against PAS in Washington vs. Glucksburg, and has provided very convincing reasons for doing so. But my friends continue to cry injustice. If social consensus is the criterion for determining right and wrong in human action, why do they not submit to the social consensus on the very issue that we are debating? They have yet to provide me with an answer (one that does not take us around in circles). But the answer is very simple. They believe that society is wrong. Therefore, they really don't believe in their heart of hearts that social consensus is the measure of good and evil in human behaviour. "If I no longer wish to live, nobody has the right to force me to live beyond my wishes. I am the master of my destiny. I am my own Lord." That is the crux of their reasoning.

It is true that some of them believe that Kevorkian's trial amounted to a miscarriage of justice, that Kevorkian was unfairly restricted in his options. But had the trial proceeded exactly the way they deem a just and fair trial should proceed, does anyone really believe for a minute that my friends would presently consider themselves fortunate enough to have finally taken possession of the moral truth about assisted suicide and would submit accordingly? No. Rather, they would continue to maintain that the majority is wrong. Society is the sum of its parts. It is not a living entity. The position that social consensus determines right and wrong ultimately boils down to "I am the measure of right and wrong". Who else could possibly be the measure of good and evil? It is either God--and they certainly won't buy into that idea--or it is society as a whole (which is ultimately reducible to individual persons, and why should this or that individual be in a more privileged position with regard to moral issues than I should?).

In short, my friends are relativists. For them there are no absolute moral principles of right and wrong. They argue that there is no basis for upholding absolute moral principles, for instance, that it is always and everywhere wrong to intentionally kill a human being (which would rule out PAS or active euthanasia, abortion, the dropping of the A-bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, to name a few). The idea of a moral law to which everyone is obliged to submit appears much too restrictive for most people today.

But the Church has always maintained that the moral law does not constitute an unnecessary restriction on a person's freedom. In fact, the moral law is the key to real freedom. Most people today think freedom is simply doing what you want without restriction. But freedom is not the ability to do what you want to do without interruption or impediment. It is actually the ability to want what you ought to want, that is, to want what is truly good for you. Let me explain. The kind of freedom specific to human beings is inexorably linked to knowledge. You are a free being because you are a rational being, that is, you have the ability to know in a way that transcends mere sensation. As knowledge increases, freedom increases, and as freedom increases, so too does responsibility.

The dog that runs free and bites the little girl playing in the park did not do so freely even though the dog was allowed to run "freely". The dog didn't know what he was doing, and so the dog is not held responsible for the bite, the owner is held responsible.

Freedom that is specifically human does not mean being able to do what I want. I am free only if I have the ability to know whether or not what I want to do truly promotes the fullness of my being, that is, is really and truly good for me. If I lack that knowledge, I am not free but rather a slave to my passions, or a victim of social custom. And so moral knowledge does not take away my freedom or restrict my freedom, rather it actually endows me with genuine freedom. If I can direct my life in accordance with the truth, I am truly free. I can only be free if I know the truth: "The truth will set you free", say the Scriptures. And of course it is not enough to know the truth, I also have to will the truth, that is, choose to live according to the truth, which is precisely what love is.

We would argue that happiness is not subjective at all. Just as "the good" is not subjective-for all things desire their own "to be"-happiness is not determined by my own desires. There are so many people in this world who pursue their own will (what they want) and are successful, and yet complain of a profound boredom, a gnawing emptiness. Why? They have achieved all that they set out to achieve. They have gotten what they wanted. They have what they worked very hard to obtain. But they complain of emptiness. Happiness is not a matter of having, but of being. It is a result of being a certain kind of person. And one becomes a certain kind of person by choosing. For it is not true that "you are what you eat". Rather, you are what you choose. There is a relationship between "doing" and "being", that is, between what we do and what we are. We determine our moral identity, the kind of person that we are, by the choices that we make. And it is very possible for us to choose a course of action that does not promote the fullness of our being, but rather decreases it to some degree. It is not possible for a dog or a cat or a plant to bring about such a state of affairs because dogs, cats, and plants do not choose at all. Let me illustrate, if I may, the situation in which humans find themselves. Below is a blank check.

There is something already there on the checks when you get them in the mail. You have your name, address, name of the bank, account number, etc. But there is also a space that is not filled in, a space the contents of which are up to you to determine. You have to fill in the blanks. Now, below is not a blank check, but a simple blank:

This is not a check. There is nothing on it. You have to fill in everything. You determine "what" this is going to be. It may be a check, or a note, a bookmark, etc. The relationship between human nature and the moral life is very much like the check, not the blank. You and I have a definite nature, that is, a human nature. But there is a space for us to determine, to "fill in" so to speak. Now we can't just fill in anything. There is a space for our signature, a space for the amount, a space for the date, etc. And we are not even free to fill in the space for the amount with just any amount. There are definite limits. And the check is a definite thing, not a love note, not a bookmark, not a fork or a plate.

It was Jean Paul Sartre who taught that existence precedes essence, and that it is through choosing that a person determines "what" he is (his essence). This position is more akin to the blank directly above. Sartre argues that there is no human nature, and so there is no norm for human choices. There are no limits to human freedom, and no limits to what I may choose. There is no moral "ought". We may define good choice as a choice that accords with my nature and promotes the fullness of that nature, but since there is no nature, there is no such thing as a good choice. And so there is no morality. Do what you want, just be ready to deal with the consequences of your choices.

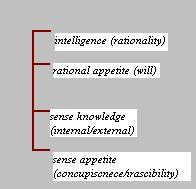

But existence does not precede essence. Existence without essence is purely unintelligible. Only a certain kind of being has existence. A being is always a "what", even a free being who has the ability to determine himself. I am a human kind of being. That is "what" I am. That is my nature. It is a different kind of nature than that of a brute animal. We have all the powers of brute animals, and more. Brute animals have external and internal sensation, instincts, sense memory, etc., but human persons have the ability to think (apprehend natures) and communicate ideas, as we are doing now. Not only are we able to know that which is beyond sensation, we can also will (desire, tend towards) that which we know through the mind.

Notice in the diagram above that following upon sense knowledge is sense appetite. The dog not only sees the red meat, he desires the meat. But humans have not only sense knowledge, but intelligence. We can see the red meat, perhaps even desire the red meat, but we may have a reason not to eat the meat (high cholesterol, diet, etc.). We have a knowledge that goes well beyond sense knowledge. We know whether or not the meat is good for us. But I thought "the good" is that which all things desire? If I desire the meat, then it is good, is it not? The meat is sensibly good. It tastes good, but it may not be intelligibly good. It may not be good for me, especially if I have high cholesterol, or if I am over weight, for instance. If I choose to give up the meat, I do so because I desire to live, or to become healthier, or protest an injustice, as in a hunger strike. The goods in question here are higher goods, not merely sensible goods. What is the difference between sensible good and intelligible good?

Brute animals only know through sensation and so only tend towards that which is known through sensation. The only goods they pursue are sensible goods. But human persons do not merely pursue sensible goods. We pursue or tend to what is known through intellection, and so we pursue intelligible goods, such as truth, or friendships, life, integrity, etc. What is intelligibly good is not always sensibly good. Education is intelligibly good, but getting up in the morning to go to school is very often not sensibly good. It doesn't feel good having to wake up early. Few of us would argue that a teacher who rarely arrives to school on time because he or she doesn't feel like getting up in the morning is simply irresponsible. Having donuts for lunch every day would certainly be sensibly good, but who would doubt that such a diet is intelligibly bad?

What are the intelligible goods? Germain Grisez, Joseph Boyle, and John Finnis have done a tremendous amount of work over the past twenty five years developing natural law as we find it throughout the history of philosophy. The following list of basic intelligible goods is based on their ideas. Note that these goods are basic or ultimate. In other words, they are not pursued for the sake of obtaining some other good. They are sought for their own sake, and so they are basic, and not instrumental.

1. Life: Human beings have an inclination to preserve their lives, to defend their lives, and they tend to beget new life because they see life as a good to be pursued for its own sake. It is good to be alive.

2. Knowledge of truth: Human persons seek truth. We ask questions, we search for a knowledge of the causes of things, not always for the sake of some further end, but often for its own sake. The sciences are a testimony to our search for truth.

3. Leisure: Human persons tend to leisure. We are inclined to behold the beautiful, and so we stop the bus to behold the beauty of Niagara Falls or the Grand Canyon, or we go for walks to behold Victorian style homes along the streets of Toronto, or visit art museums or listen to beautiful music. Experiencing the aesthetic perfects us as human beings.

We also leisure in another way. We tend to develop skills and we seek to perfect those skills. Not only do we tend to behold the beautiful, we also tend to create beautiful works of art, for instance paintings, poetry, prose, music, etc. We invent games, such as chess, hockey, football, etc. We develop skills and seek to perfect them because doing so perfects us as human beings.

4. Sociability: We seek harmony between others and ourselves. We seek friendships, and we seek peace between nations. The most frequent cause of suicide seems to be loneliness. And the very word "person" implies community, for the word comes from the Latin "per" (through) and "sona" (sound), which refer to the phenomenon of communication or language. A person communicates, that is, enters into community. We tend to do so because relationship perfects us as human beings. As John Donne wrote: "No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a part of the continent, a piece of the main. When any man dies, it diminishes me. Therefore, do not seek to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee."

5. Religion: Human beings also tend to seek harmony between themselves and a "totally other" source of meaning, which some call the gods, or God. All cultures seem to evidence a tendency towards this type of harmony. We see this in pagan rites, the sacrifices to the gods, burial rituals, mythology, and in the great religions of the world.

6. Integrity: Human beings tend to seek harmony between the various elements of the self. As Grisez, Boyle, and Finnis write: "For feelings can conflict among themselves and also can be at odds with one's judgments and choices. The harmony opposed to such inner disturbance is inner peace. Moreover, one's choices can conflict with one's judgments and one's behavior can fail to express one's inner self. The corresponding good is harmony among one's judgments, choices, and performances--peace of conscience and consistency between one's self and its expression." (The American Journal of Jurisprudence. 1987, Volume 32, p. 108)

7. Marriage: Marriage is a basic intelligible human good that human persons seek for its own sake. All love tends to unity, and conjugal love tends to a total giving of one's physical self to another. It is a joining of two into one flesh union. And because it is a total self-giving, marriage is a permanent and exclusive union (a love that is divided is not a total self-giving).

These goods together constitute human well-being. The realization and integration of these goods is precisely what is meant by a good life. But happiness isn't just a matter of having these goods in your life. For example, you are healthy, educated, you appreciate the beautiful, you have hobbies and other skills, friends, religion, and you are married, and you have no serious internal conflicts. But you are good if you will the good, not just your own good. Basic human goods are tendencies of human persons. Willing the realization of my own good only does not constitute a good will. I am (being) a good person by virtue of my willing the good, and "the good" is not limited to this individual instance which is myself. Nor is it limited to my immediate family, or my relatives, nor is it limited to all those whom I know. If I will "the good", I do so wherever there is an instance of it, that is, I will the good of all human persons.

For as we said above, you are what you choose, that is, you are what you will. We shape our moral identity by the choices that we make. I determine myself to be a certain kind of person by my choices. If I am to be a good person, I must choose in accordance with the good. The good, as we said, is fullness of being. Moral integrity involves a will to integrity, that is, a will towards the integration of these goods in human persons. A good will is a will towards integrity (integration of the goods), towards unity (unification of the goods), towards being (fullness of being). An evil will is one that is not entirely ordered towards integration. An evil will is not open to "fullness of being". It is disintegrated, and so an evil will is a disintegrated character. We will try to explain this in more detail in another question.

Happiness is a matter of choosing well. It is a matter of being because it is a matter of choosing. It is very difficult to convince people of this. When people begin choosing in accordance with the good (intelligible good) and not simply in accordance with their feelings (sensible good), they begin to experience a certain happiness that comes from within (a fulfillment). They begin to experience a certain integrity. It is a different experience than the experience of a passing pleasure, or of excitement. It is more enduring, more interior and less likely to be disturbed by circumstances beyond our control. Just as an atom is more stable than a meson (for it has more being), so too is happiness more stable than pleasures. I asked the entire class if they would choose to spend their entire summer holidays at a Neurology Wing of a hospital hooked up to a machine that stimulates certain sections of the brain, causing the sensations of intense pleasure, even sexual pleasure. Imagine, the entire summer holiday experiencing non-stop pleasures. Not one person said they would choose such an alternative. Such a course of action was referred to as a "waste of the summer holidays". Why? The answer is that human persons find meaning in performing specifically human acts, and specifically human action aims not simply at pleasurable sensations, but at the achievement of intelligible goods. It is by a loyal devotion to these that one finds meaning in life.

We can't give anyone a piece of this meaning or happiness like we can a piece of pie. It does not come ready-made. It is self-determined. A person has to begin choosing well before he begins to experience human well being. Nevertheless, it may help to take a good look at people of moral integrity and note whether or not they seem happy people. And take a look at those who have everything they want, but who "weigh up the prospects of life and death" and fail to consider the one thing that alone is important. Are they happy people, according to their own words?

"You are mistaken, my friend, if you think that a man who is worth anything ought to spend his time weighing up the prospects of life and death. He has only one thing to consider in performing any action-that is, whether he is acting rightly or wrongly, like a good man or a bad one. " (Socrates)

Return to Articles Page.